You may not, understandably, have heard of the Spanish poet, essayist and novelist Juan Goytisolo (1931 – 2017). But he was in fact considered Spain’s greatest living writer at the beginning of the 21st century.

Rewind over sixty years to 1954 and he travelled extensively through Almería province in Andalucía, then the poorest region in Spain, producing a travelogue, Campos de Njiar, in conversation with locals he met and stayed with along the way.

Published in 1960, the book is a fascinating insight into the incredible changes that have taken place in a very short time in Spain – and especially Andalucía.

My own foray into Almería was an attempt to follow in these footsteps, living for eight weeks in a small farmhouse in Huebro, Nijar in 1950s conditions.

The idea? To test out my newly acquired permaculture skills, and trade my M&S charity shop slippers for tomatoes, olive oil and wine. The wine, in fact, was a local brew that looked like an oaked rosé, tasted of sherry laced with brandy, and was washed down with homemade pig’s blood tapas and salted young olives. That was just the beginning.

The white-washed houses of Nijar in Almería province, the subject of Goytisolo’s book, are steeped in Moorish history. The municipality is also renowned for its ceramics and textiles and sits at the foot of the Sierrra Alhamilla, on the edge of the Cabo de Gata, Natural Park.

Almería itself (capital city of the province) has been named Spain’s gastronomic capital for 2019: if that excites you, a good place to start would be the historical Bar Casa Puga, a tapas bar opened in 1870 (Calle Jovellanos 7 barcasapuga.es).

On Cortijo Living

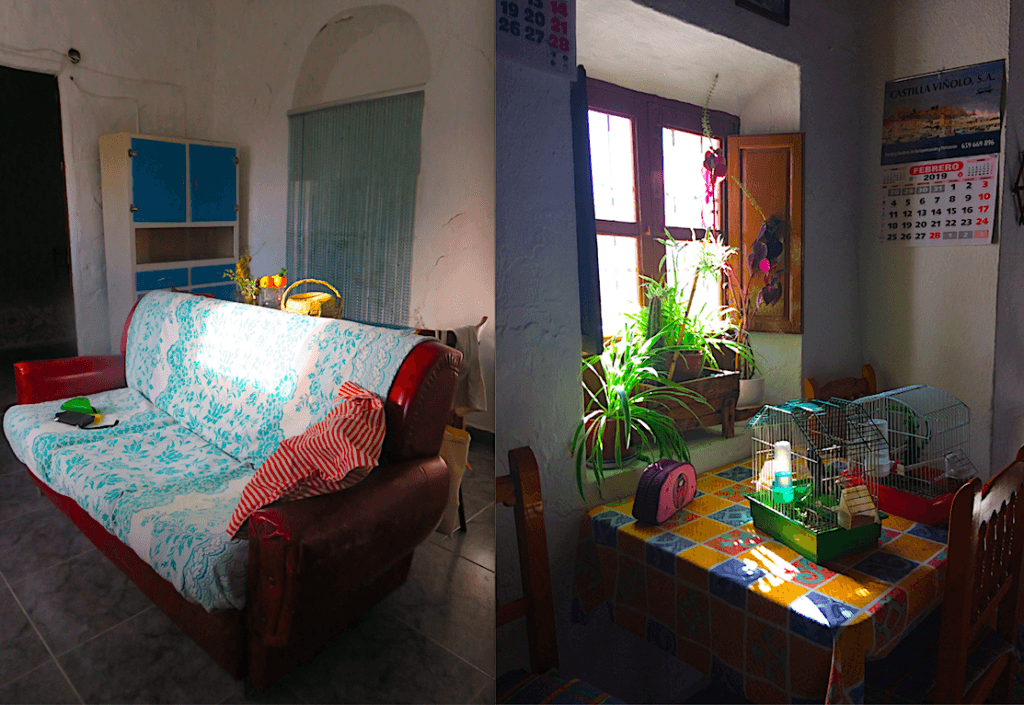

So what’s a cortijo (farmhouse) actually like? My basic dwelling with attached pigsty in Huebro was at the foot of the Sierra Alhamilla mountains. Daily chores included bringing fresh drinking water from the mountain spring and collecting wood for the fire, as well as washing bed linen and clothes in the cold-water stone tank by hand. I foraged for oranges, lemons and almonds fallen from the tree, along with rosemary, thyme and lavender found growing wild on the mountainside.

Local Bounty

It was a 5km round trip by foot to Nijar, the nearest village down the valley, following the 500-year-old aquifer installed by the Moors and still used today. Known as the Ruta De Agua, it provides natural spring water to the cortijos in the valley below. My walk to the local shops to stock up was a rough path down the gorge; not for the faint hearted (and no supermarket carrier bags or shopping trolleys in sight). I also enjoyed eating pimentoes grown by Enriquetta and made vegan stew (see pic above) secretly at home in the cortijo. If you declare your vegetarian credentials here, you’re met with a raised eyebrow, given a quizzical look – and then served chicken.

Carmen & Enriquetta

These two are the strong women of Al Andalus (pic below), the backbone of village life, fierce, hardworking and loyal. They remain holding the fabric of life together in harsh mountain conditions.

Vistas

Every morning I would watch the early sunrise over the cemetery (see pic below), the palms providing much needed shade in the valley, the Tabernas desert around the corner.

Cowboy Culture

To see Almería in the movies, watch The Good, The Bad, The Ugly (1968) by Sergio Leone (music by Ennio Morricone). It’s a key film in the Dollars Trilogy, which established the idea of the Spaghetti Western.

What is Permaculture?

It isn’t just about gardening: it’s a holistic design philosophy and framework for creating innovative, sustainable ways of living, coined in the mid-seventies in Australia by David Holmgren and Bill Mollison. It’s an ecological system that embraces both visible and invisible structures helping us find solutions locally and globally for earth-care, people-care and future-care.

It also encourages us to be resourceful and self-reliant on a personal level but also in our homes, gardens, communities and businesses; initiated by cooperating with nature and caring for the earth and its people. It’s not exclusive, its principles and practice can be used by anyone. By working with nature and carefully considering our resources we can be more productive, generative, exploring the myriad of possibilities of using less.

More info on staying in a cortijo: cortijosmanzano.com. For more about Julia Riddiough’s work see: juliariddiough.com

Main image: Julia Riddiough