I’ve hiked the perimeter of several London boroughs, including – over an arduous six hours – Camden’s whopping 17 mile circumference.

History surely dictates, however, that the capital’s origin be attempted. Not just a mere borough, the City is actually the smallest UK county (since 1132), the second smallest British city in population and size (after St David’s in Wales) and, most famously, the richest square mile in the world.

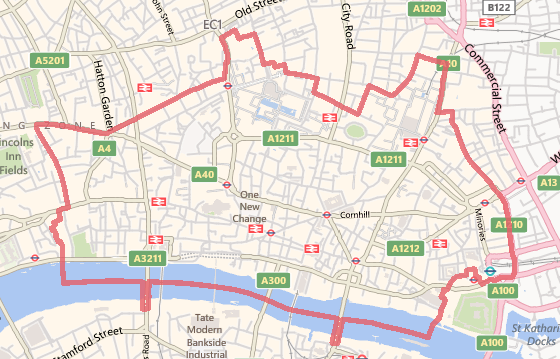

Our starting point is near Farringdon station; below is the approximate route. GPS will do the rest.

1. Wander Chancery Lane

On a nippy Saturday morning we start the moderate six-mile walk at an arbitrarily-chosen northwest corner of the City: Chancery Lane Tube. Sunrays pierce the tinted windows of office blocks, and pillows of cloud shadow our steps as we pass the hangar-like Smithfield market (named after the ‘Smooth Field’ outside the city walls), where meat has been traded for 800 years.

In a nod to its infamy as former site of execution, a butcher flashes a smile, cleaver in hand, whilst across the road, thirtysomething couples swish past to brunch, broadsheets under one arm.

2. Admire Golden Lane

The Barbican tower, built between 1965 and 1976, looms above Farringdon like a grubby fishbone, and we’re soon pattering round its adjoining forest of concrete, the City’s largest residential area (4000 people in 2000 flats). Lesser known but lovelier is Golden Lane Estate, to the north, built earlier by the same architects (Chamberlin, Powell and Bon), with striking panels in primary colours. And along the shopping parade, we smile at the Barbie-like pink font of Barbican Greengrocers.

3. Snake round Moorgate

Yet it’s all so silent. If, in the countryside, silence is the sound of rest, or isolation, in the city it possesses an ambiguous quality, and the empty streets around Moorgate provoke eerie, other-worldly thoughts about the layers of dead beneath our feet, the plagues, bombs, tube crashes, fires (the Great Fire of 1666 destroyed four-fifths of the City). In short, all this seems to underline life’s transience.

4. Ponder Bishopsgate

But on Moor Lane our quietude is slashed by the hypertrophy of civilisation: the whir of cranes, yells of builders, roar of trucks, and the scrape of metallic barriers, like fingernails on a blackboard. Is the City saying ‘enough’? We crane our necks at a towerblock, its windows like gills.

The north-eastern tip of the perimeter brushes against Hackney. It’s a brief stroll down Norton Folgate, where playwright Christopher Marlowe lived in 1589, and onto Bishopsgate, the beauty of Hawksmoor’s Christ Church rising in the far corner of Spitalfields, just beyond our boundary. (All the while Liverpool Street station yawns on our right.)

There’s a real sense of the old City wall as we snake around Middlesex Street, Widegate Street, Goodman’s Yard. London Wall was built by the Romans in the late 2nd century but has largely disappeared, whilst the current boundary has expanded over the years. Near the Tower of London (itself in the borough of Tower Hamlets) we spy two surviving sections (the others are near the Museum of London and St Alphage).

5. Stand still on London Bridge

The City’s boundary runs bang down the centre of the river, though it controls both Blackfriars and London Bridges, so we race over to find the black bollards with trademark Dragon insignia that mark its southern tip. On London Bridge, families with pushchairs survey the saturnine view and, as clouds sail above the water like steamships, I imagine the Monday morning rush hour, observed by TS Eliot so clearly in The Waste Land:

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Oscar Wilde was blunter still: “To me the life of the businessman who…catches a train for the city…is worse than the life of the galley slave. His chains are golden instead of iron.”

We make one diversion away from the perimeter up to the City’s only Hawksmoor church, the elegant St Mary Woolnoth, built in 1716 from the proceeds of coal tax. As trains rumble deep into the clay beneath its foundations, its belfry rises like the prow of a boat.

At the western boundary with Westminster two wonderful dragons stand on either side of the Embankment, defiant against a sudden blue sky. A bronze plaque informs us that they represent a “constituent part of the armorial bearings of the City of London” and were mounted above the entrance of the old coal exchange, demolished in 1963. Even more ornate is the entrance at Temple Bar on Fleet Street.

We’re back at Chancery Lane three hours after our start and, about to dive into the cavernous Cittie of Yorke pub, glance over at the cranes perched like question marks over the City’s prosperity.

There’s no question about walking back to where we live, however, and we’ve soon left the oddly other-worldly environs of the UK’s smallest county – and are satisfyingly on the tube home.

Support us if you can

With the sad demise of our free monthly print titles across London last summer due to advertising revenues in freefall, we now need your support more than ever. Every contribution, however big or small, is invaluable in helping the costs of running the websites and the time invested in the research and writing of the articles published. Please support Weekendr here for less than the price of a coffee – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

.